Money, money, money in a central bankers world

Report by: Ben Jones Published: 8th November 2022

Key points:

- Controlling money supply is key to influencing the price level

- Adjustments in the general price level take time. It’s highly unusual for high inflation to disappear quickly

- Inflation has often come in waves and this decade may easily see a repeat

I recently wrote a piece highlighting the importance of restraining growth in money supply when trying to fight inflation. You can find the link here.

However, I wanted to go a little further into the theory behind it and what it means for inflation today. Central Bankers, not least Christine Lagarde, have expressed their complete shock that the combination of monumental injections of both fiscal and monetary stimulus have led to inflation. I think most people (excluding Central Bankers) are aware that endless money printing will ultimately devalue the value of that money, but nevertheless, it’s still worth understanding the ideas behind it and the implications of it.

The argument that money supply is the greatest component of inflation is the core thesis of the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM). It proposes the idea that the general price level is an equilibrium between real output and the money supply, and that the price level is proportional to money supply. Any change in either money supply or real output can change the price level equilibrium, the change of course being inflation or deflation.

The formula developed by Irving Fisher was MV = PT

where M = money supply, V = velocity, P = price level, T = volume of transactions of goods and services

Let’s suppose one day that the Government just doubled the amount of money in everybody’s bank account, all else being equal. Everybody feeling flush with cash would run to purchase goods and services. This would start to bid up prices (inflation would run high). There will be substitution between goods too, perhaps everyone initially goes to buy steak for dinner and steak prices jump rapidly. At some point, people will move towards relatively cheaper chicken. Over time, people will substitute between goods until they eventually drive the prices of all goods higher. Given no change in real output for any good, eventually the price of everything will move to double what it was. At this time, the price level is in a new equilibrium between the new money supply (doubled by the government) and real output (unchanged). Once the price level is in equilibrium there is no need for further price changes and inflation disappears. While you may think that it is possible for businesses to continue raising prices, any dollar spent on something is a dollar that can’t be spent elsewhere. So yes, there may be some discrepancies in price changes across individual goods, but businesses have little ability to drastically alter the general price level. Price gouging by businesses is often the target of politician’s blame, and of course there will be examples of it. However, squeezed individuals cannot afford higher prices across all goods and will be forced to cut back spending. The competition between entirely different goods makes continued gouging unprofitable. Businesses will try to maximise profits at all times, through both inflationary and non-inflationary periods, yet this argument is often heard during periods of inflation.

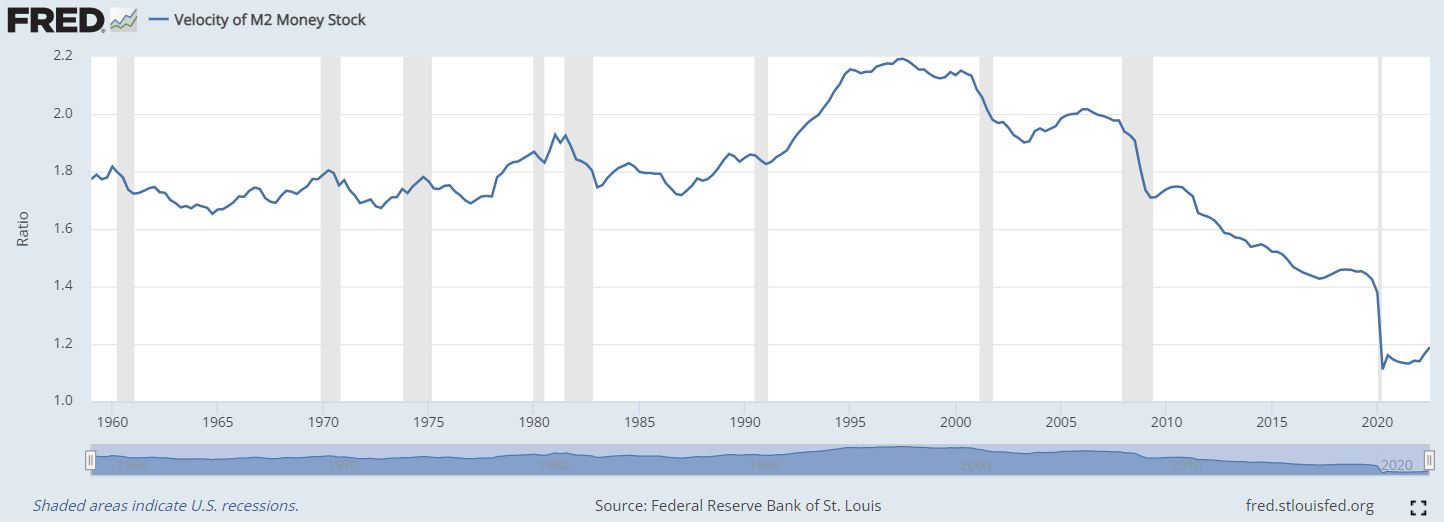

We’ve yet to mention velocity, which can be thought of as the number of transactions over a given time period. Think of a dollar bill passing hands as consumers and businesses conduct transactions with each other. Mathematically, velocity = nominal GDP / money supply. We have assumed so far that velocity remains broadly constant given spending by individuals is habitual and ought to not change significantly. Over the last couple of decades velocity has fallen lower. This has largely been driven by the fact that most money creation from 2008-2020 was via monetary policy and injected straight into the financial markets. Without much fiscal stimulus, this money remained invested in securities in the accounts of the wealthy. In other words, velocity was very low. Those dollars weren’t passing hands every day, they were simply sat invested in securities. It has played a part in explaining the asset inflation and lack of goods inflation seen over that period. Fiscal stimulus is more effective at directing money to lower and middle classes who have a higher propensity to spend and a lower propensity to invest. This generates more activity in the real economy over the financial economy. Since covid, there has been both large fiscal and monetary stimulus which has kept velocity flat over the last year. If monetary stimulus is withdrawn without the withdrawal of fiscal stimulus (which appears the most likely outcome), then I would expect velocity to move higher over the coming years.

US velocity of M2 money supply has tumbled to all time lows over the past 2 decades but a combination of tighter monetary policy with continued fiscal deficits ought to push velocity higher over the next few years.

US Velocity of M2 money supply

Source: FRED

The general price equilibrium is simply determined by supply and demand. If money supply and real output of goods and services increase at the same rate, there is no reason to expect inflation. However, a desire by politicians to spend money and run deficits needs to be financed, and this is nearly always done through inflation. This is why annual increases in money supply typically exceed annual real GDP growth and why we have become accustomed to a world of regular, low inflation. Enough inflation to finance deficits, but not so much as to cause loss of confidence in a currency.

The importance of this is that inflation doesn’t need to be ‘crushed’ by a Central Bank. It requires some control over money supply, time, and an understanding that inflation is the transition between price equilibria. Once the new price equilibrium has been realised, inflation will subside. All that would be required of a Central Bank is that they ensure that the growth in money supply is moderated. Any tools used by the Fed (quantitative easing/tightening, adjusting interest rates, reserve requirements, capital ratios and other regulatory changes) exist to influence money supply which in turn influences the general price level.

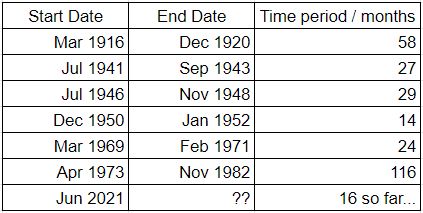

How long can it take for the price level to transition from one equilibrium to another? A look at previous inflation spikes gives us an idea of how long inflation can remain elevated.

Table source: Ben Jones Investments Data source: St Louis Fed

The range is vast from 14 months in the early 1950s to 116 months throughout the entire 1970s stagflation episode. However, one thing is clear: inflation doesn’t disappear quickly. The time also depends on how tightly growth in the money supply is controlled. For example, broad money supply fell through 1920 and 1921, which helped kill the post WW1 inflation and induce deflation. Similarly, tight control of money supply through 1947 and 1948 brought inflation down relatively quickly post WW2. During the 1970s, despite the Fed raising rates, money supply was never particularly tightly controlled, with growth rates hovering between 5-10% per year for most of the decade. In 1979, Volcker expressly targeted credit growth and eventually brought inflation down. Today, the Fed has good control over money supply which now runs at 2% YoY. If the Fed continues to keep money supply growth below 5% YoY, historical precedent would suggest inflation should fall over the next 12 months.

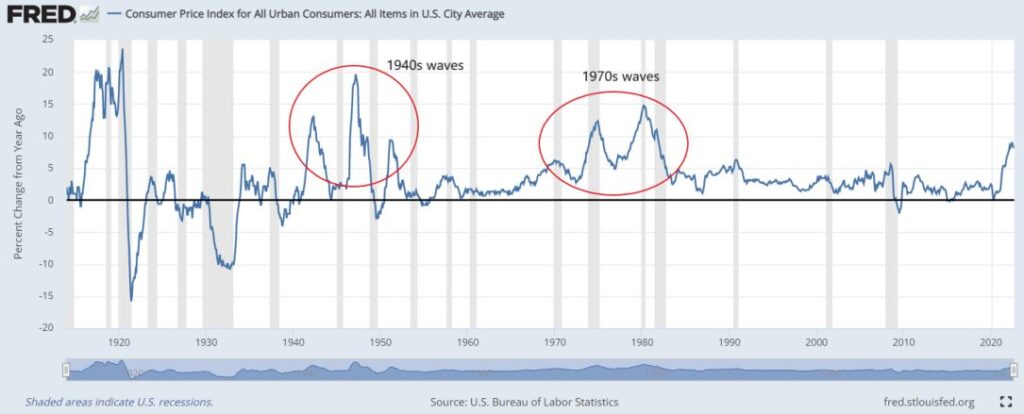

However, such restriction in credit growth deliberately slows the economy and causes recessions. This often forces a Central Bank to back away from tightening policy as it walks the fine line between deepening recession and managing inflation. This policy was poorly managed in the 1970s and was referred to as ‘stop-go’ policy. The Fed, seeking to bring down inflation, would over-tighten and cause a recession. Then, looking to ease the impact of recession, would over-ease and allow inflation to resume. It’s like an oil tanker constantly over-steering both ways and failing to achieve their goal of going in a straight line. The constant over-tightening and over-easing resulted in waves of inflation separated by recessions. Stop-go is a policy the Fed should seek to avoid at all costs. However, Powell’s comments in the latest Fed meeting about over-tightening to bring inflation down and then easing to mitigate an economic downturn has all the hallmarks of stop-go policy. It’s something I will continue to watch closely but this raises the probability of stagflation and makes waves of inflation a more likely prospect.

Waves of inflation are also more likely when underlying issues are not fixed. Right now the world faces a myriad of issues, including: deliberate currency debasement to aid high debt burdens, war in Europe, a decoupling between the US and China that may reverse globalisation, energy security issues, concerns of dollar hegemony across much of the developing world, and underinvestment in commodity production. This is just a few among many! Further threats such as a Chinese invasion of Taiwan or nuclear war in Europe remain. It is unlikely that many of these issues will be resolved within this decade and that certainly opens the door to multiple waves of inflation, as seen in the 1940s and 1970s.

Inflation Waves

Source: St Louis Fed

So what does all this mean for asset prices?

Waves of inflation make for a highly choppy environment. Historically, stagflation is positive for commodities and commodity related equities. Given the Fed’s control over money supply so far, and the lag between policy and economic data, I suspect we’re nearing the peak of the first wave of tightening. This would be a good time to tactically buy treasuries. Equities would benefit from a pause in Fed tightening but I expect an earnings recession to act as a drag on the market. Strong businesses and statistically cheap businesses should be favoured in such an environment.