it's the money supply stupid Why Money Supply is the Key to Tackling Inflation

Report by: Ben Jones Published: 27th October 2022

Key points:

- Constraining growth in money supply is the key to tackling inflation

- Money growth can be restrained at rates lower than prevailing inflation. In other words, tackling inflation does not require rates to be above CPI

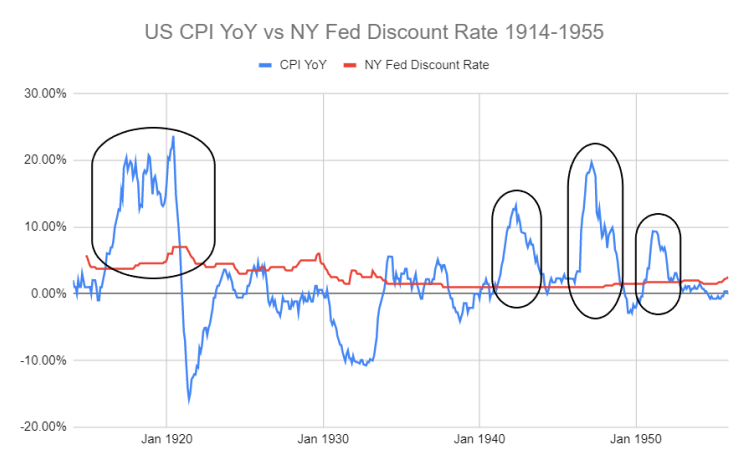

- 1920, 1942, 1947 and 1951 are all examples where inflation was resolved without short term rates exceeding CPI

- Fiscal restraint helps bring down the level of interest rate required to restrict growth of broad money

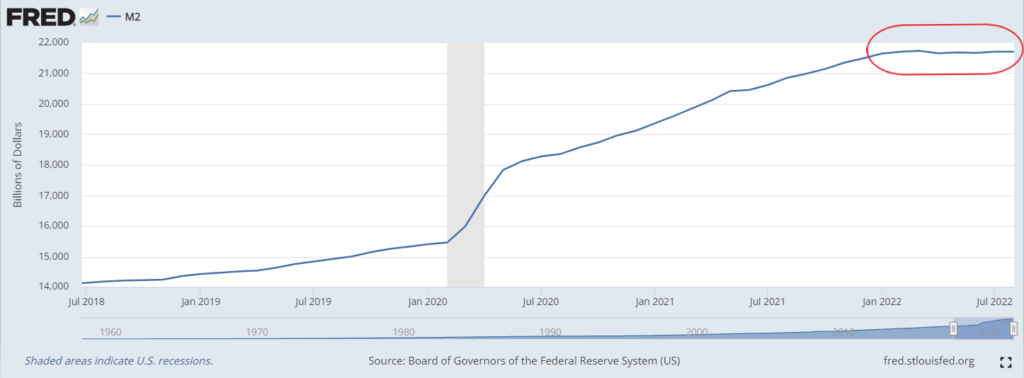

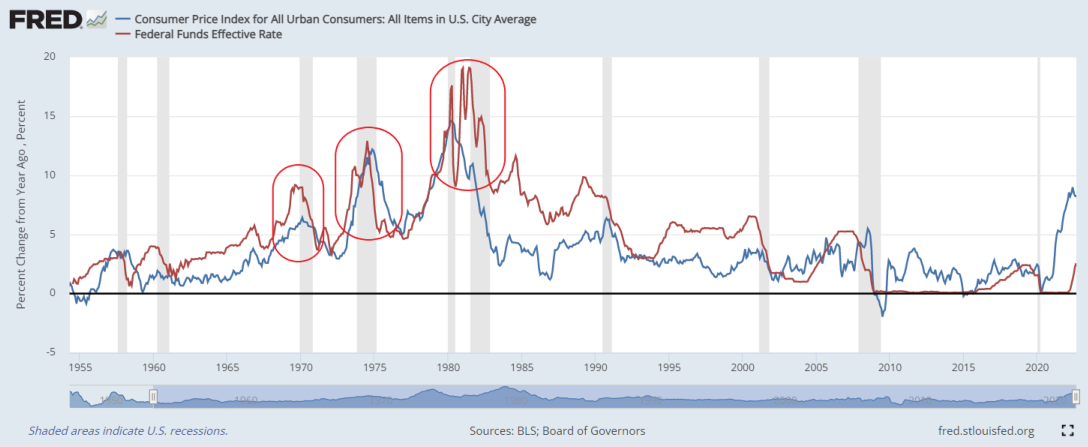

A recurring theme is that the Fed Funds (FF) rate must exceed the level of inflation to bring it down. This is often accompanied by a chart (shown below) that points back to the 1970s and notes that every peak in CPI was met by a higher peak in the FF rate. However, going back a little further in history shows that this isn’t always the case and that inflation can be brought down while rates remain relatively low. The salient point discussed in the article is that it’s not the absolute level of rates that matter, it’s the level of rates required to restrict growth in money supply that matter.

FF rate vs CPI in the 1970s

Source: FRED

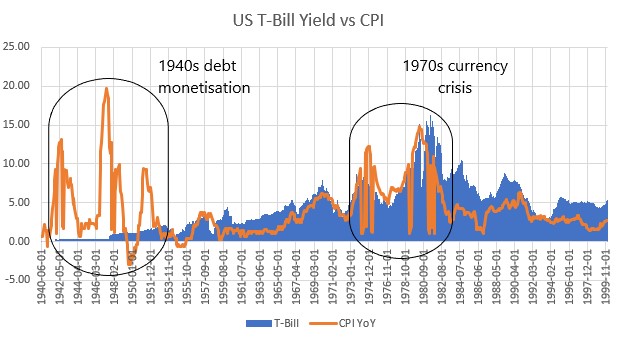

Chart source: Ben Jones Investments Data source: St Louis Fed & Bloomberg

You could be forgiven for thinking that holding long term rates at 2.50% with inflation at 20% was a recipe for hyperinflation, but no. There are a number of reasons why the US did not experience hyperinflation and why credibility in the Government and Federal Reserve were maintained despite real rates of -17%. These reasons include the US’s position as the clear global economic and military power at the time, the dollar’s status as reserve currency, the removal of a general price cap in 1946, the dire predicament of all other developed economies post WW2 and their need to borrow dollars to rebuild their war-torn economies. However, there is another factor that was vital in tackling inflation that is often overlooked, and that was the restriction in the growth of money supply.

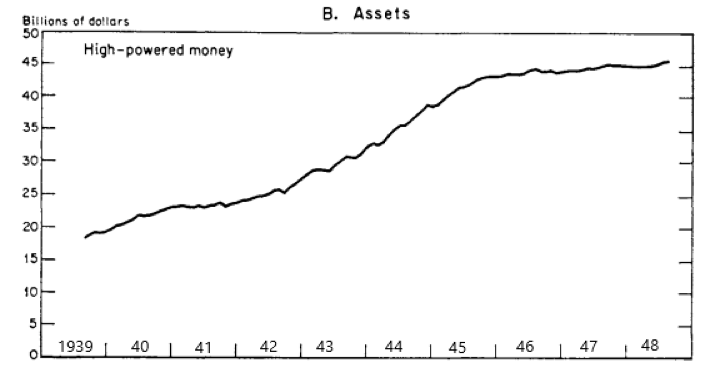

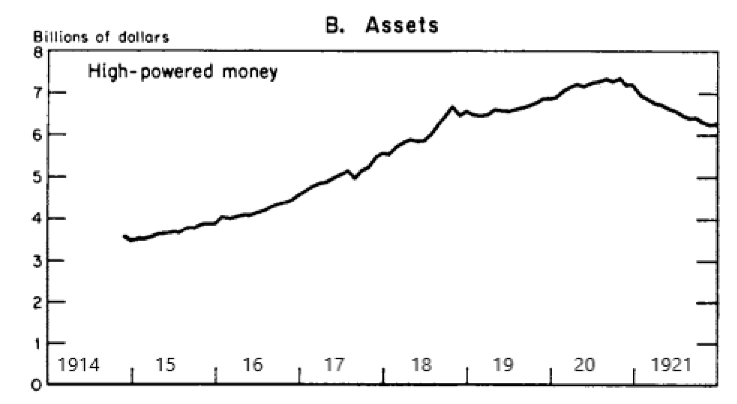

Source: Milton Friedman & Anna Schwartzman: A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960

But how did the Fed limit growth in money supply and maintain low rates? The Fed used the reserve requirement ratio to restrict bank lending and limit the growth in credit. If the reserve requirement is raised, banks must hold more cash against any loans they make. Under fractional reserve banking, this limits the money multiplier effect. For example, with a 10% reserve requirement ratio, a bank must hold $10 as reserve for every $100 of assets. The remaining $90 are lent to businesses and consumers where they’re deposited at other banks. Those banks then lend $81 of the $90, holding $9 as reserve. This goes on until the $100 of original assets are held against loans of $900, totalling $1000 of money. Raising the reserve requirement to 25% would limit growth of that original $100 to $400. This tool was used with great effect by the Fed in the late 1940s to restrict growth in the money supply and reign in inflation. The reserve requirement was raised from 20% to 25% throughout 1947 and 1948. There was also an increase in the margin requirement on security purchases from 40% in 1945 to 100% by 1946, meaning no money could be borrowed to purchase assets. Both of these measures contributed to the restriction on growth of money supply.

Source: Ben Jones Investments (chart) ; NBER (data)

We can see below the impact of raising the discount rate was sufficient to induce a broad drop in money supply, despite the discount rate topping out at 7% in the face of 20% inflation.

Source: Milton Friedman & Anna Schwartzman: A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960

Inflation Today