modern monetary theory (MMT) gone but not forgotten

Report by: Ben Jones Published: 14th December 2022

Key points:

- Open discussions around MMT have died down following the highest levels of inflation in 40 years

- Monetising debt and debasing currencies to fund excessive government spending are policies that have been used throughout history

- MMT is correct in much of its key theory but fails to provide adequate solutions to its greatest failings

- While I think MMT will remain quiet during the current inflationary episode, it must operate subtly in the background

- The best protection from MMT is the ownership of hard assets

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) may have temporarily disappeared from the public arena, but it is still subtly being used to address an existing debt crisis and will continue to be used over the next decade.

In order to understand why, it’s necessary to grasp the fundamental ideas of MMT. These are:

- Government deficits don’t matter because governments can print the money they spend. It follows that national debt doesn’t matter much either, as long as it is denominated in a country’s own currency.

- Government overspend is indicated by inflation and not by deficit or debt figures

- Government deficits are the other side of the coin to private wealth

- Taxation forces the use of a currency

In other words, the key aspects of MMT are that governments should fund necessary projects – infrastructure, healthcare, defence, education – and need not worry about the cost as long as it is paid for in a currency that the government can print. There are elements of truth to this. It is true that the Treasury can print paper dollars. The Federal Reserve can create reserves out of thin air and use these reserves to purchase US government debt. This keeps rates low and allows the government to effectively self-fund. Interest paid on debt owned by the Fed would accumulate as profits for the Fed which are then remitted back to the Treasury anyway. In effect, the Treasury pays interest to itself.

It’s an appealing thought – governments being able to spend on public services without concern for the cost of those services. If printing money to fund deficits is such a great idea, why hasn’t it been suggested before? Well it has… the ideas around currency debasement are as old as money itself. The truth is that there really is nothing modern about modern monetary theory. We can look back to Dionysius the Elder, ruler of Syracuse around 400BC, who racked up huge debts financing wars against the Carthaginians. In order to manage his debt, he forced all citizens under pain of death to turn over any silver one drachma coins and re-stamped them with a 2. Ta-dah! Debt halved. The Romans lowered the gold and silver content of coins and increased the proportion of base metals to devalue the coin without changing its face value. This was done to fund wars and led to rampant inflation within the Roman Empire. Henry VIII of England cut the precious metal content of coins in order to fund wars and a lavish royal lifestyle. The first uses of paper money in China from 1000AD resulted in the return of coinage as unbacked paper money was printed excessively and became worthless. The point is that currency debasement being used as a method to finance government spending is an ancient practice, there’s nothing modern about it.

We have been taught to believe that a small amount of inflation is a good thing, but why? Well inflation is a stealth tax and transfers wealth from savers to borrowers. The largest borrower of course being the government. Yet too much inflation risks loss of confidence in a currency, government and central bank and can lead to financial instability followed by significant public outrage and riots. One need only look through examples of Weimar, Zimbabwe and Venezuela to see the damage caused.

If we compare deficits from decades ago to GDP today, it looks easy to monetise them. For example in 1970, the US ran a deficit of $3 billion. Today nominal US GDP is $23 trillion. The deficit in 2021 was $1.8 trillion. Could that look equally as small against US GDP in 30 or 40 years time? In other words, should we just expect future growth to accommodate current deficits? Well most of the growth is accumulated inflation. We can see from the chart below that GDP today is 10x higher than real GDP since 1947.

US nominal gDP vs real GDP (Both indexed to 100 in 1947)

Source: FRED

Average real growth per year since 1947 is 3.0%

Average nominal growth per year since 1947 is 6.4%

The difference is inflation which comes out at 3.4% per year.

In other words, the use of inflation as an effective tax on all dollar savers and earners has allowed GDP to become 10x higher than it otherwise would be and this has dwarfed deficits run from decades ago. Another way to think of it is that the government was able to spend $3bn on real goods and services in 1970 that would be worth far more than the $3bn they would need to pay back today. The reality is that low, regular inflation has allowed governments to run larger deficits which have been paid for by ordinary people suffering an average loss of purchasing power of 3.4% per year. It’s why we’re taught that low, regular inflation is a good thing. It’s why Central Banks set low but positive levels of inflation as a policy goal. They want inflation to be high enough to allow for higher government spending but low enough to not cause public unrest.

WHY DID MMT COME TO PROMINENCE

If there’s nothing new to MMT, why the more recent hype before inflation came crashing down on it? Well, for a couple of reasons. Firstly, before 2021 we hadn’t seen any significant inflation for 40 years leading to remarkable complacency that inflation was a beast of the past, never to return. In the wake of the financial crisis, the Fed were aggressive in their use of monetary policy, cutting rates to zero and engaging in QE programmes that hadn’t been seen since WW2. Despite zero rates and continued QE programmes, inflation didn’t appear. This led to overconfidence that globalisation and technological development were overwhelmingly deflationary and that expansionary monetary policy would not be enough to overturn the deflationary effects. Of course, the critical ingredient missing was the combined use of monetary and fiscal policy (which is inflationary) and was the policy used to tackle covid in 2020.

The second reason is that just like Dionysius, the Romans and Henry VIII, there is always a desire from both people and politicians for governments to spend more money. And how should that be paid for? By cutting spending elsewhere or raising taxes? No. Why do that when you can simply print the money? Of course there is no such thing as a free lunch and the reality is that people pay for this through the loss of purchasing power on their money (ironically a regressive tax that hurts the poor the most). Widening income equality has also pushed calls for government to do more to support the working classes. Yet the political unpopularity of raising taxes or cutting spending elsewhere has forced governments to resort to the easiest solution… print the money and debase the currency. MMT became seen as an obvious and inevitable solution.

ISSUES WITH MMT

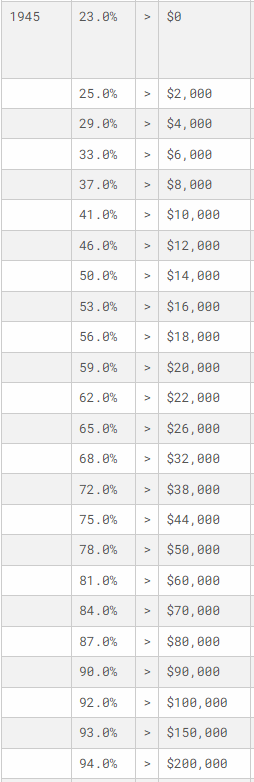

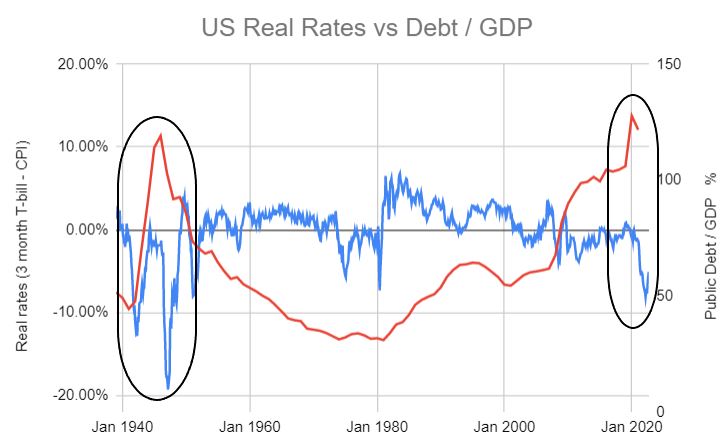

MMT advocates will argue that they never suggest reckless, unchecked spending as a legitimate policy, but simply that inflation must be the judge of overspend. For as long as inflation remains low, there are no issues. Print and spend. However if spending starts to drive inflation higher, MMT suggests it is best tackled with higher taxes to drain excess money from the system. While I would agree the theory is broadly correct, it would never work well in practice. You would have to tell an electorate that despite inflation eating away at their quality of life, they would need to pay more taxes on top. It is politically infeasible to do this if you have any plans on winning another election. We haven’t seen any significant tax increases across developed countries with the exception of the UK. Even in the UK, the tax hikes have been nowhere near large enough to reduce the debt/GDP level. The US today has a government debt level around 130% of GDP, similar to its immediate post WW2 peak. Following WW2, we saw real rates (3 month t-bill yield – CPI) hit -19% at their lowest with top rates of tax reaching 94%. These measures did work back then but so far today we have seen no political appetite at all to risk such low real rates or raise taxes to anywhere near the same degree. US income tax brackets from 1945 is an example of the political response to tax policy when debt was last at its highest relative to GDP.

Data source: https://taxfoundation.org/historical-income-tax-rates-brackets/

Using CPI since 1945, $10,000 back then is equivalent to about $167,000 today. That does mean the majority of these bands are targeting high income earners. Although 23% on the first dollar earned is a steep opening bracket that would squeeze low income workers.

The major issue with MMT is not so much its fundamental principles, but the fact that it provides no adequate solution to the problems it can cause. As we’ve discussed, raising taxes in response to higher inflation is not politically viable. If governments fail to tighten policy significantly enough on the fiscal side (through raising taxes or cutting spending), then the heavy lifting must be left to monetary policy. This would require higher for longer rates that very much do pose a problem for high levels of debt. We’re starting to see that with Japan today who cannot raise rates because the higher interest payments on a debt that is 262% of GDP would keep the debt figure spiraling ever higher. They have used yield curve control for 6 years now. A policy where the Central Bank (Bank of Japan) will actively purchase JGBs in the open market to cap their yields at a pre-determined level. This keeps the nominal (and real) cost of servicing debt low. Even in the US, with debt/GDP of 130%, an average interest rate of 5% would put annual interest payments at ~1.6 trillion per year. That is more than defence and education spending combined. This won’t be affordable over longer periods of time and will force many years of negative real rates ahead in the US. This will play out over the coming decade as either above average inflation, below average rates or a combination of the two.

We see below that as debt/GDP rises, it becomes necessary for real yields to become increasingly negative.

Chart Source: Ben Jones Investments Data Source: St Louis Fed

Whilst I argue that currency debasement has been used by governments since the beginning of money, MMT does go the extra step by openly advocating for it. It’s one thing to know that your purchasing power is going to lose 2-3% per year, it’s another to be told that destruction of purchasing power is a tool that will directly be used to finance government spending. This ought to immediately cause concern to anybody holding that currency. In the past, outright debasements have forced people away from fiat and towards foreign currencies or hard assets. Gold ownership was banned in the US in 1933 before FDR formally announced the devaluation of the dollar in 1934. Market moves against currencies broke the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system in 1971 and forced the pound from the ERM in 1992. Today, Turkey struggles to protect its currency from high inflation and a leader opposed to higher rates. MMT argues that taxation forces people to use a government currency but that by no means anyone must hold that currency over long periods. Taxes and government decree may give a currency reason to exist, they provide no reason for a currency to have value. A currency’s value comes from confidence in its government and central bank. It comes from economic growth, productivity, low levels of corruption, contract enforcement and an educated population. Aggressive moves to deliberately debase a currency can push savers to dispose of it by any means necessary and purchase other assets that better protect purchasing power. These assets can include real estate, precious metals, foreign currency, other commodities and equities. Governments may move to ban the purchase of certain assets as a way of protecting their own currency. While it’s normal and straightforward to purchase many of these assets in the West, it’s not the case in developing or frontier economies. Developed countries with strong economies and financial systems with a track record of relative currency strength retain more confidence. However, countries without the track record can’t think of attempting to openly use MMT as a tool.

WHY MMT HAS RETREATED IN CURRENT CRISIS

A policy of ignoring deficits forces currency devaluations and MMT fails to adequately recognise the dangers associated with loss of confidence in a currency or provide a realistic solution. It’s a slippery slope; and once you’ve slipped, it can be a difficult path back. This has become more evident over the last 12 months as global inflation has soared in nearly all global economies, with many experiencing double digit inflation. MMT’s solution of tax hikes has been exposed as a limited solution at best. Politicians and Central Bankers have tried to defend the strength of their currencies. It becomes more obvious which Central Banks are caught in the debt trap as their monetary response is slower and less aggressive (note the ECB and BOJ).

WILL MMT RETURN?

The reality is that most developed economies are indebted to the point where financial repression becomes necessary (typically government debt/gdp > 100%). While MMT has taken a back seat due to its failings with inflation, it is always the go-to tool for reducing debt burdens. As such, it will continue to lurk in the background. I do not think conversations around MMT will be as overt as they were before 2020 and I don’t expect to see politicians or economists openly calling for debt monetisation while inflation remains high. They must try to persuade the public that their currencies are strong. However, politicians will secretly try to take advantage of currency debasement that has supported larger government spending since the world broke away from the gold standard. Stealth inflation is a far more politically feasible way of taxing the people than raising taxes directly or cutting spending on services. Fiat currencies will continue to be debased, and hard assets will continue to provide the best protection from this.