managing inflation why the fed is right to be behind the curve

Report by: Ben Jones Published: 10th March 2022

Key points:

- The Fed needs to monetise debt while maintaining confidence in the dollar

- This requires a significant period of negative real yields and financial repression by Central Banks

- The 1940s Fed policy was dictated by a high need to monetise debt at a time when confidence in the dollar was naturally very high

- The 1970s Fed policy was dictated by a high need to retain confidence in the dollar at a time when debt monetisation wasn’t particularly important

- Today is more like the 1940s than the 1970s, and the Fed’s approach should reflect that

Normally a comment like ‘the Fed is behind the curve’ is made with negative connotations and is often spoken in the same sentence as ‘policy mistake’. The idea that rising inflationary pressure isn’t met with aggressive tightening must be a ‘mistake’ from ‘complacent’ Central Banks. However, this isn’t always the case and today isn’t the first time in history that Central Banks have deliberately been slow to tighten policy in the face of rising inflation. The reason that the mainstream view of fighting inflation is to tighten aggressively is because our last memory of inflation was Paul Volcker’s combative action in 1980. Only those now in their 60s could watch this unfold before them as adults – the rest of us must go to history books instead. Yet if we keep those history books open and flick back a few pages to the late 1940s, we learn about a very different approach to inflation – an approach that is more appropriate for the situation we find ourselves in today.

During an inflationary period, the most important rate is not the Fed Funds rate or the 10-year nominal yield, it’s the 10-year real yield. I’ll be using the real yield based on the 10-year minus actual inflation (CPI headline rate). I acknowledge the value in using breakevens for analysis given they are forward looking, but data only goes back to 2003 and it’s easier to use actual inflation for comparisons to the 1940s and 1970s. Breakevens are also projections and don’t reflect the full reality of how events panned out.

A Central Bank’s decision on how to manage real yields is based on two key goals:

- Managing debt monetisation

- Retaining confidence in its currency

Monetising debt effectively requires very negative real yields but keeping confidence in a currency may require positive real yields. In the 1940s, the more important task was monetising debt. In the 1970s, the more important task was retaining confidence in the dollar. Today, monetising debt is the more important of the two tasks – that’s not to say that can’t or won’t change in the future, but as things stand today, I would most certainly assert that’s the case. We’ll explore below the situation in the 1940s, the 1970s and why the lessons are important today.

Debt Monetisation

Debt monetisation hinges on a government being able to print their own currency and having debt denominated in their own currency. This applies to the US because the Federal Reserve can create dollars and all US debt is denominated in dollars. It doesn’t apply quite so much to a country like Argentina who can print pesos but have a significant chunk of their outstanding debt denominated in US dollars. When Argentina struggles to pay back dollar denominated debt, they can’t print the dollars and must negotiate with creditors in the same way a defaulting business would. When the debt burden gets too high, those who can monetise debt simply have their Central Bank create reserves and purchase government securities. This helps to boost the money supply and artificially keep nominal interest rates low. If money supply is expanded at a rate greater than real growth, there is essentially an excess supply of money that reduces the value of it. Given debt is a promise to pay back a fixed nominal amount of money, any reduction in the value of money reduces the value of debt denominated in that currency. Inflation measures the loss of value in money relative to a basket of real goods. It’s why all sensible bondholders (lenders) must consider the expected loss of purchasing power when assessing at what nominal rate they should lend, to ensure they generate an appropriate real return. For borrowers the opposite is true. It is excellent to borrow money if the amount paid back in future is much less in real terms than when they took out the loan. Given the government is the largest borrower, they benefit the most from ensuring that real rates are negative such that nominal returns paid on debt are lower than growth (even with 0 real growth, inflation alone will push nominal growth above nominal rates). This is why real rates must remain negative in the US for some time. The only reason real rates will turn positive is either when sufficient debt has been monetised and/or inflation is beginning to destroy confidence in the dollar and the Fed must restore confidence by lifting nominal rates enough to make real rates attractive to lenders.

Debt monetisation is not new by the way, there are countless examples that stretch back to 400BC. Dionysius the Elder was the Greek ruler of Syracuse, Sicily from 407-367BC who spent years racking up large debts on military campaigns to conquer other cities. When lenders became concerned about his ability to repay and stopped lending money; Dionysius responded by requiring all citizens of Syracuse hand in their drachmas. He then stamped every 1 drachma coin with a 2 – lo and behold, his debts had been halved. Now in reality, this doesn’t come without complications. Such action risks causing a loss of confidence in the currency and it risks lenders never lending to you again which in the long term is extremely damaging. However, there have been successful examples of currency devaluation. In the 1930s, FDR devalued the dollar against gold by re-setting the price of gold from $20.67/oz to $35/oz. This was accompanied with large fiscal stimulus in the form of public works programs that put Americans to work. The result was a successful rebound from the destructive deflationary spiral of the Great Depression. It didn’t result in a loss of confidence in the dollar and the US continued to cement its place at the top of the global economy a decade later.

Debt monetisation becomes necessary when debt reaches levels at which it can’t be repaid – historically for Governments, this tends to be a debt / GDP ratio of 100%+. At this level, other courses of action are no longer effective. The other courses of action would involve higher taxation / reduction in government spending / default. Without going into detail here, the economics of these options don’t work effectively enough to tackle the problem and the lack of political will from many make implementations difficult.

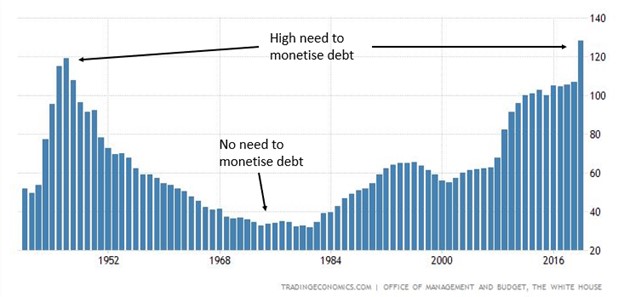

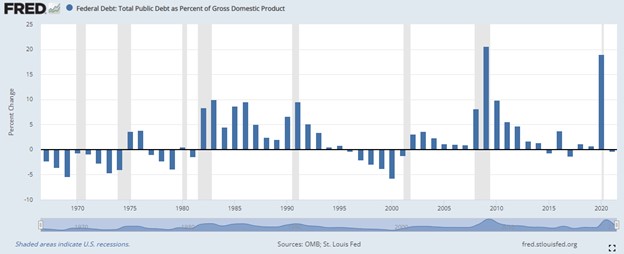

Debt monetisation in the 1940s was a necessary policy due to the very high debt / GDP incurred post WW2. We can see from the chart below that US debt / GDP peaked at 120% in 1947 before dropping in the 50s – 70s and has been rising since, hitting a new record of 136% in 2020.

US Government debt / GDP

Source: Tradingeconomics.com ; Ben Jones Investments

In the late 1940s, the sheer scale of combined fiscal and monetary stimulus pushed inflation up to nearly 20% in 1947. Despite this, the Treasury ordered the Fed to keep long bond yields below 2.5% because the Treasury couldn’t afford higher interest payments on such a large national debt. Yes, real rates hit -17%. And yes, despite 20% inflation, the Fed was still actively purchasing Government securities. Today we think it’s crazy for the Fed to still be actively engaged in QE with 7% inflation, and for what it’s worth I don’t think the Fed should still be engaged in QE now, but I am pointing out that the Fed has continued easing before despite higher inflation levels.

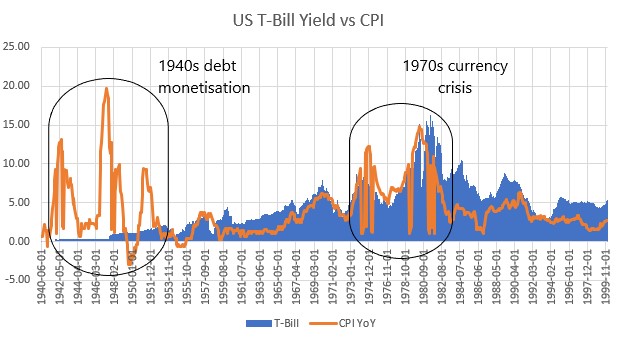

The chart below shows the key differences in policy between the 1940s and the 1970s. Clearly debt monetisation was the key goal for the Fed and Treasury in the 1940s and yields were kept near zero despite higher inflation. Debt monetisation wasn’t a concern in the 1970s and it was more important for the Fed to retain confidence in the dollar, hence the high-rate policy employed by Volcker (and to a degree Burns before him).

Chart source: Ben Jones Investments Data source: St Louis Fed & Bloomberg

Debt was less of an issue in the 1970s. If we look back at the chart of US debt / GDP, we can see that debt levels through the 1970s were fairly low. This is because considerable debt monetisation took place through the late 1940s and early 1950s. In fact, for half the time real yields were negative from 1940-1980. With debt / GDP below 40% through the 1970s, debt monetisation was not an issue. By far the greater issue was retaining confidence in the dollar and this is why the Fed’s reaction to inflation in the 1970s was very different to its reaction in the 1940s.

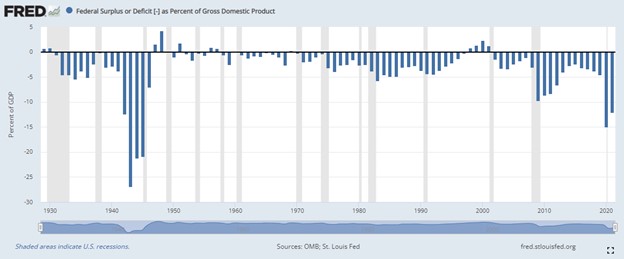

Debt monetisation today is important. US debt / GDP topped out at 136% in 2020 – the highest in US history. The government has run continuous budget deficits since 1970 (excluding a 4 year period from 1998-01).

Even through non-recessionary periods, the US has been running a budget deficit of 3-4% per year. During recessions the budget deficit rises and hit a post WW2 high of 15% in 2020 as the US tackled the Covid-19 crisis.

Annual US budget deficit as percentage of GDP

Source: St Louis Fed

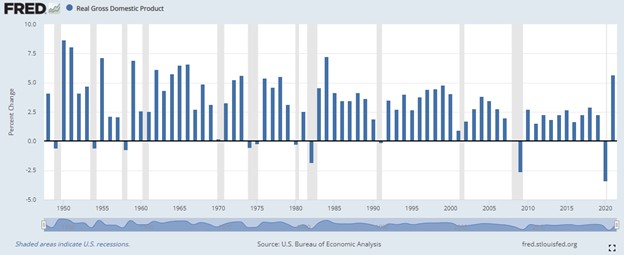

In the meantime, real GDP growth has normally been around 3% per year through non-recessionary periods and negative through recessionary periods.

US real GDP growth

Source: St Louis Fed

In non-recessionary time, with deficits and growth running at similar levels, debt / gdp can either grow a tad or shrink a tad. However, every recession pushes debt much higher whilst real GDP either shrinks or stalls. As a result, there is limited ability for US debt / GDP to shrink but there are occasional recessions which push the ratio much higher.

US public debt / GDP , YoY change

Source: St Louis Fed

Naturally this means that over the last 60 years, the debt / GDP has been continuously rising… can that go on forever? In the words of Herbert Stein, ‘If it can’t go on forever, it will stop’. I don’t see how debt can grow to be infinitely larger than GDP but trying to predict at what point it should create an issue is no easy task. I would simply argue that I am not aware of a single historical example of a country’s debt / gdp exceeding 100% without experiencing some form of debt monetisation. This would suggest the Fed is poised to follow the 1940s instruction manual and keep rates low despite mounting inflation.

Currency Confidence

Since 1971, fiat currencies have had no physical backing at all. The previous monetary system from Bretton Woods in 1944 through to Nixon closing the gold window in 1971 involved the dollar being fixed against gold at $35/oz with other currencies then pegged to the dollar in a fixed exchange rate system. Whilst fiat currencies today have no physical backing, they are backed by an economy, a market and a government. Why do people have confidence in the dollar today even though there is minimal gold behind it and dollars are just pieces of paper with the faces of former prominent politicians printed on them or recorded numbers on a bank ledger? The reason is that the US is the world’s largest economy, the world’s most politically influential force, it has a strong military and the world reserve currency. The US is a world leader in technological advancement with the world’s largest and deepest capital markets, a history of relatively competent governance with reliable contract enforcement in fair courts, a culture of success and entrepreneurship. These are all reasons that people seek to live and work in the US or grow businesses there. All of this involves earning and operating in US dollars. These are now the factors that determine confidence in a currency, more so than its backing by gold. Maintaining confidence in a currency is absolutely vital when a Central Bank seeks to combat inflation, but most people tend to underestimate just how much confidence can be retained even through periods of blatant currency debasement.

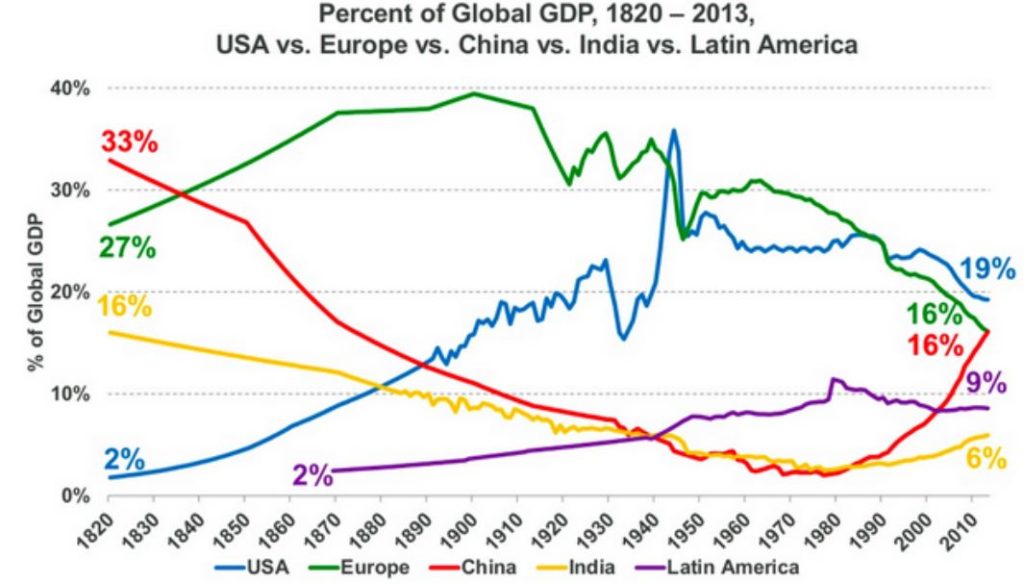

Confidence in the dollar in the late 1940s was incredibly strong. The dollar had started taking over from the British Pound as the world’s strongest currency after WW1 but formally cemented its status as the world reserve currency at Bretton Woods in 1944. By the end of WW2, the US was comfortably the leading global power and Europe and Japan sat in economic ruin. In 1945, the US was the world’s largest economy, accounting for 35% of global GDP. They led the allies’ negotiation at Yalta and played the largest roles in the creation of the IMF, UN and World Bank that were all formed at the end of WW2. They had financially supported the allies throughout WW2 through the lend-lease program which provided supplies and weapons to allies without demanding payment until after the end of the war. The US Treasury also held 20,000 tonnes of gold in 1945 which was about one third of the world’s government owned gold and comfortably the world’s largest single holding.

Given the financially desperate state of the rest of the world post WW2, the Marshall Plan was activated in 1948 which offered loans to Europe and Japan to help them rebuild their destroyed economies. They were in such financial difficulty that they would gratefully accept any dollar offered to them by the US. This was the first step in activating the dollar as the internationally used currency. It ensured more global trade was done in dollars, it gave foreign countries dollars to purchase American goods and the dollars were so desperately needed that it didn’t matter that inflation in the US was 20% with nominal yields being held at 2.5% by the Fed. The US could debase the dollar significantly and the rest of the world would still have needed them. This is why it made sense for the US to monetise debt to such a great degree – it reduced the national debt burden without any serious threat to their currency or credibility.

The 1970s was very different. Nixon rocked the international monetary system so severely in 1971 that it broke the fixed exchange rate system and led to the floating rate system that we have today. Under Lyndon Johnson’s ‘guns and butter’ spending plans that grew US deficits, a recovered Europe became sceptical that the US could continue to run such large deficits without devaluing their currency. Scepticism was often led by France, with then French finance minister Valery Giscard d’Estaing describing the dollar’s reserve status as an ‘exorbitant privilege’. The US could purchase goods from all over the world and simply print the money to pay for it. By 1967, the US had $36bn of foreign liabilities and only $12bn of gold reserves. European countries were growing fearful of a dollar devaluation and requested gold from the US Treasury in return for their dollars at $35/oz as stipulated by Bretton Woods. From 1966-1970, France, Germany, Belgium, the UK all sent dollars to the US Treasury requesting gold in return. At one point, France sent a warship packed with dollars to New York and waited until the dollars had been unloaded and the warship loaded with gold. At first the US Treasury satisfied these demands to continue the appearance of a strong dollar. In 1945, the US Treasury had 20,000 tonnes of gold, by 1971 European requests had drained the Treasury down to around 8,500 tonnes. A request from the Bank of England in 1971 was the straw that broke the camel’s back. The Treasury refused and shortly after Nixon announced that the US would not redeem gold for dollars any longer. This was a default on the national debt. Paul Volcker, who served as undersecretary of the Treasury for international monetary affairs at the time, commented “If the British, who had founded the system with us, and who had fought so hard to defend their own currency, were going to take gold for their dollars, it was clear the game was indeed over.” Just prior to the closing of the gold window, concern around the dollar was so high that meetings took place at the IMF without the US delegation to discuss an alternative reserve currency. The proposed solution was for the IMF to create SDRs (Special Drawing Rights) that could be used as a reserve should the dollar falter. Whilst we won’t cover SDRs here, the key takeaway is that plans were actively being drawn up to replace the dollar as reserve currency. This demonstrates how little confidence the world had in the dollar at this time.

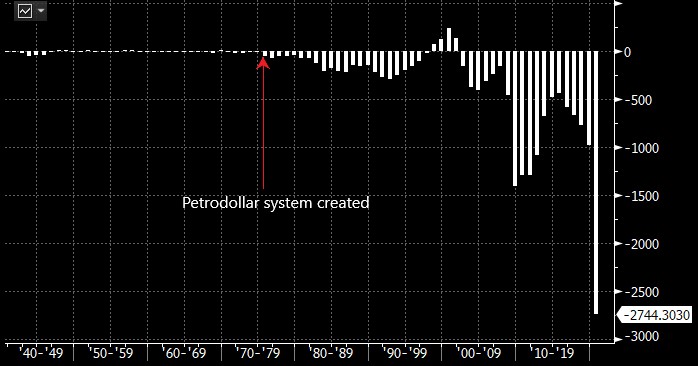

When the gold window was closed and an oil crisis exacerbated inflation in 1973, the primary concern of the US Treasury was to retain confidence in the dollar. This was paramount to the US global leadership position and retaining the ‘exorbitant privilege’ it has enjoyed now for nearly 80 years. To do this, capital had to be encouraged to remain in the dollar despite high inflation. One key way of retaining capital is to ensure it pays to hold dollars. In other words, real yields need to be positive and the Fed needs to demonstrate a tough approach to protecting the value of the dollar. Even this wasn’t enough to protect the dollar. The US kickstarted the petrodollar to ensure the dollar was still being widely used and held internationally. An agreement was struck between the US and the Saudis – the Saudis would sell all their oil in dollars only and invest the proceeds in the US (holding US treasuries); in return the US would provide security. This deal was vital in rescuing the dollar’s reserve status. It ensured the dollar was the world’s primary traded currency and that the international community would continue to hold dollars. This allowed the US to purchase goods from the rest of the world on credit whilst supplying dollars to the rest of the world. You can see in the chart below how US deficits soared following the petrodollar agreement.

Annual US Government budget surplus / deficits in USD billions

Source: Bloomberg

Confidence in the dollar was a crucial reason why the Fed took different approaches to monetary policy in the late 1940s and the 1970s.

Where does confidence in the dollar rest today? I would argue it’s stronger than the 1970s but weaker than the 1940s. The advantage for the USD today is that every country in the world is currently engaged in currency devaluation, including the EU, the UK, Japan and China. There are also huge question marks hanging over any alternative to the USD. The USD hasn’t been backed by gold since 1971 but it is backed by more than nothing – the US itself. Today the US is still the largest global economy, arguably the most innovative, the most politically influential, the most powerful military, it has the largest and deepest financial markets ruled by a capitalist and stable set of laws with good governance and a fair mechanism for disputes in court. There isn’t a country that competes with all these attributes, although China is certainly the one that is closest to competing. China’s economy has been growing more quickly, as has their sphere of influence via the Belt and Road initiative. Although their influence is more limited to Central Asia and Africa. China’s attitude to Uighur muslims, their opacity over the origins of Covid and their wolf-warrior diplomacy demonstrated against Australia has not endeared them to the West. China’s only potential ally of reasonable power is Russia. China still has capital controls and has shown a capricious nature in its dealings with businesses and business owners. There is little confidence that laws can be stable and that foreign individuals would see a fair dispute in court were they arguing against the interests of the Communist Party. There has yet to be a truly economically successful example of a communist regime and I’m still sceptical that China will achieve this under the communist direction of Xi Jinping.

However, the dollar will face increasing competition in years to come. China has put in motion steps that begin to undermine the dollar as a reserve currency. The Belt and Road initiative has forced international use of the RMB and encouraged trade in that currency and demand for it. It has also increased pressure on countries receiving those loans to be politically more sensitive to China’s demands. This is very similar to the Marshall Plan in 1948 that initiated the international use of the dollar following Bretton Woods. China also set up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) which could make loans to projects around Asia. AIIB can most certainly be viewed as a competitor to the World Bank and Asia Development Bank which are more heavily dominated by the US and Europe. China is also working alongside Russia to develop an international payments system that would rival SWIFT. Yes it would help both countries mitigate the impact of economic sanctions, but it also provides other countries with means of making international payments outside of dollars or a US dominated system. Over the past few years, Chinese commodity exchanges have seen higher volumes with the introduction of more commodity futures contracts priced in RMB. The issues mentioned before still stand but it’s also clear that China is taking measures to one day challenge the dollar.

Which metrics indicate to us that there is still confidence in the dollar? Breakeven rates and the dollar index both offer clues.

US 10-yr breakeven rate

Source: Bloomberg

The 10-year breakeven chart tells us what average annual inflation rate the market expects over the next 10 years. Right now it’s 2.47% – only mildly above the Fed’s 2% long run target. Personally I think this rate is too low and we’ll see a higher average level of inflation transpire, but the market doesn’t seem concerned about the long term prospects of inflation at the moment. If confidence in the dollar is lost, I would expect to see breakevens move much, much higher as markets price in the possibility that inflation may remain very high for a long period of time.

US dollar index

Source: Bloomberg

We can also look at the dollar index which measures the dollar against a basket of currencies (most notably the euro). Right now, the dollar index is at a comfortable level and isn’t showing weakness against other currencies. This would suggest that despite higher inflation in the US than the EU, capital is not fleeing the dollar in favour of other currencies. It’s true that every country is debasing their currency, but that only means that the US can get away with debasement to a greater extent than it otherwise could. There is no currency alternative. The obvious alternative is hard assets like gold, real estate, commodities, land, equities (particularly value stocks) and whilst generally the prices of these are rising to reflect currency devaluation, there aren’t signs of panic in these markets. Another giveaway is watching how the dollar reacts to higher than expected inflation prints. The initial reaction has been dollar strength on higher CPI prints driven by higher yields on the expectation of Fed tightening. This makes sense if you’re confident that Fed tightening will eventually bring inflation back down. If you were worried about higher inflation prints leading to persistently high inflation or possibly hyperinflation, you would immediately sell the currency on higher inflation believing that higher rates would fail to solve the problem. For example, at the height of Weimar hyperinflation, nominal rates reached 21% per day. Yet even rates of 21% per day wasn’t enough to encourage anyone to hold the Mark. People found more value burning paper notes for warmth. This isn’t to say that confidence can’t be lost in the dollar, but it is to say that we’re not seeing it yet.

What should the Fed be doing now?

Looking back at history, we can establish that debt monetisation today is vital and confidence in the dollar is currently ok. This doesn’t mean the Fed should be complacent, but it does favour a policy more in line with the 1940s than the 1970s. It’s also important to note that inflationary periods last years and that’s normal. Historically, it would be highly unusual for inflation to settle down towards 2-3% by the end of this year and stay there.

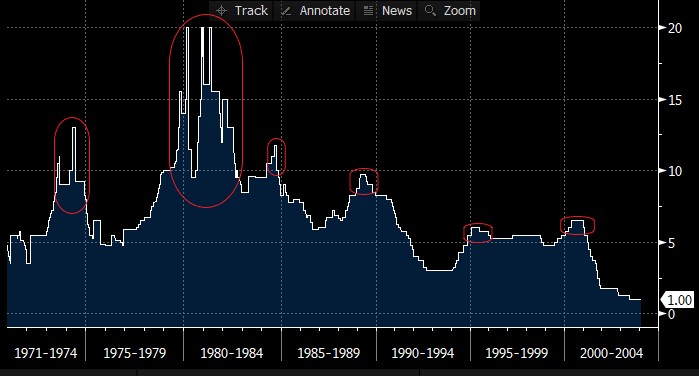

The ideal aim for the Fed is to be as far behind the curve as they can without falling off the back of it. That is to say, they need to monetise debt to the greatest degree they can without triggering a crisis of confidence in the dollar. It’s a fine line to walk, and one that has historically proved incredibly difficult to manage successfully. Most often a Central Bank will bow to pressure from the people and from politicians to tighten excessively to end the pain of inflation. I think the most appropriate action for the Fed to take from here is to hike rates 4 times per year at 25bps per hike. If inflation gets into double figures or persists at high single figures, action can be taken to shrink the balance sheet alongside the gradual rate increases. If inflation subsides and/or the economy shows signs of tipping into recession, then the Fed will pause the hiking cycle. The market is pricing 7 hikes this year with JP Morgan calling for 9 – I’ll be very, very surprised if we end up with that many. There have been comments among market participants of 50bp hikes – I think this action would be overly aggressive. Large hikes are designed to shock the market and economy when the Fed wants to shock it. These shocks happen at the end of a hiking cycle when the situation is viewed as critical by the Fed and typically lead to recession. The chart below shows larger hikes – you can see that they took place at the end of hiking cycles in 2000, 1979 and 1974. If the Fed hikes 50bps early in the cycle and it fails to tackle inflation, it could create panic among the market that questions the Fed’s ability to kill inflation and forces the Fed to overtighten.

If the Fed feels that confidence in the dollar is being lost, then more aggressive hiking that includes 50bp hikes will be required. Given the necessity of monetising debt, the Fed will view this as an emergency measure and will be very reluctant to do this until absolutely necessary. Considering the Fed was still engaged in QE in 1947 with 20% inflation, I am not convinced single digit inflation over the next few years will be deemed an emergency. I think we would need to see double digit inflation to warrant Volcker-esque tightening. That’s not to say it can’t happen, but I expect the Fed to be moderate in their tightening until that happens (if it does).

Fed Funds rate, 1971-2004

Source: Bloomberg

A key hurdle that the Fed and the Government will face is political pressure from people hurt by the effects of inflation. It’s no secret that those hurt most by inflation are the working class – those who spend the highest proportion of their earnings on necessities and own the fewest assets. The decline in real wages can fuel strikes and protests. It becomes incredibly difficult to tell a squeezed population that the best course of action is to do less, not more. People want to see action taken to combat inflation which may include rate hikes. The reality is that it would likely bring about a recession that doesn’t help the working class either. Given the greater impact on the working class, the increasing wealth divide piles more pressure on social cohesion and the Government’s responsibility to address it. During these times, the Government needs to be conscious of wealth distribution and consider progressive taxes (particularly taxes on capital) that may help to address it. This can be done in line with tax relief designed to benefit low-income workers to avoid a generally high level of taxes.

The reality is that whichever route the Fed chooses, it’s going to be heavily criticised. If the Fed chooses debt monetisation by remaining behind the curve, inflation will remain higher for longer and that will inflict pain on working Americans. This pain will be directly blamed on the Fed, even though all things considered, it’s the least bad option. If the Fed is too heavy handed in its dealing with inflation, they will be criticised for creating a recession that impacts the American working class. I am sceptical that the ‘soft landing approach’ of lower inflation with no growth concerns is feasible – in fact, there isn’t an historical example to date of inflation reaching 7.5% without it being deemed an inflationary crisis or resulting in a recession through Fed policy tightening. There was talk late last year of the ‘goldilocks’ scenario where inflation subsides and growth remains strong – history tells us it would be naïve to assume this as a base case.

The outcome will be a generally more inflationary decade that will accompany persistently negative real yields, and investors should prepare for that.

Please note that this was written prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. There is no doubt that this has the potential to drive inflation higher while hampering growth. Nevertheless, the lessons from history discussed in this article continue to be highly relevant.