gold report chapter 3 The Debt and Inflation Trap that will ultimately Drive Gold Higher

Report by: Ben Jones Published: 9th October 2021

Key points:

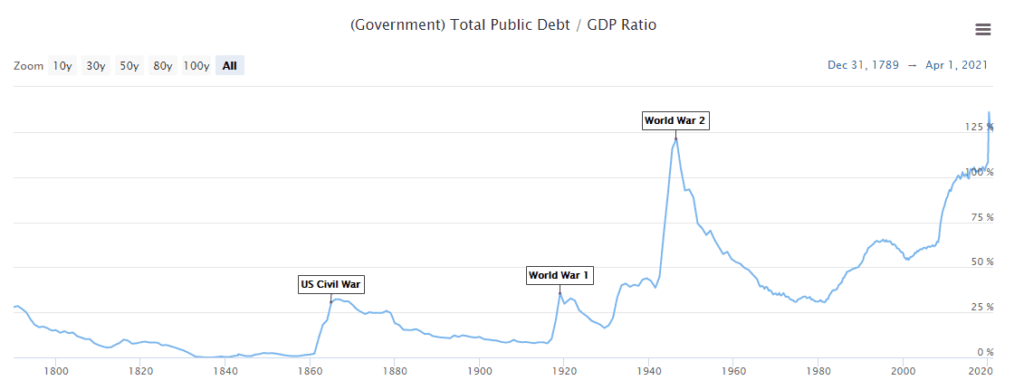

- US debt/GDP is 125% and at all time highs surpassing the WW2 peak. There is no way to reduce the debt burden without monetising it

- Debt monetisation requires real yields to remain negative

- M2 money supply increased by 25% YoY in 2020 – the highest on record. Never before has money supply increased beyond 10% YoY without generating inflation

- There are factors which suggest inflation is likely to persist rather than prove transitory

- The Fed is actively encouraging higher inflation – but will it push it too far?

Government debt/GDP is too high - it has to be monetised

For nearly all developed countries today, debt/gdp levels are higher or near to their all time highs, comparable with debt levels at the end of WW2. After WW2, the US reduced its debt/gdp from 120% to under 60% through a combination of higher taxes and inflation. Studies estimate that taxes contributed to 1/3rd of the decline in debt with 2/3rds down to inflation. These debt burdens are now too large to pay off unless the currency is devalued. This involves a country keeping growth rate – real yields > deficit rate. Reducing the deficit rate isn’t easy, it would involve spending cuts and/or higher taxes which are politically implausible. However nominal growth rates can be boosted by inflation and real yields can be pushed more deeply negative through higher inflation. It’s a transfer of wealth from savers to borrowers (with the government being the biggest borrower of all). It’s the policy that’s being employed and truthfully it’s the only realistic policy left available to the majority of developed countries. We also know it’s being employed because for the first time in history, Central Banks are actively pursuing higher inflation targets, changing their policy from targeting 2% to average 2%. The Fed led with this last August followed by the ECB a few months later.

Source: https://www.longtermtrends.net/us-debt-to-gdp

The fundamentals for gold remain very strong and will continue to do so simply because every country is plugging the economic hole left by covid with huge fiscal stimulus. The US ran a $3.1tn deficit in 2020 which at 15% of GDP, was the highest since 1945. The expected deficit in 2021 is 3.0tn and Biden is eyeing up a further 3.5tn of additional spending. Even the CBO (Congressional Budget Office) expect the Government to run $1-2tn deficits per year for the next decade and they don’t take into account any hiccoughs that might occur along the way. The US has consistently run deficits for nearly 20 years (the last budget surplus was under Clinton in 2001) and the deficits need to be monetised. There are 4 ways to reduce the national debt:

1. Default

2. Have the economy grow at a greater pace than the debt

3. Austerity – cut spending and/or raise taxes

4. Monetise the debt.

1. Default is not palatable for the US or any global power, it would completely undermine any trust in the government and their financial system, making debt issuance expensive and attracting capital flows difficult. It would seriously threaten the USD as the world reserve currency and their capital markets as the number one destination for global investment flows. Beyond that it would be considered a national embarrassment that the world leader cannot politically accept.

2. GDP growth exceeding deficits is not realistic, since 2008 GDP growth has averaged the 2% mark whilst deficits have typically run at closer to 5%. Then we have certain years like 2020 where we had a deficit of 15% of GDP whilst GDP itself contracts 6% year over year. Often debt raised by a government is not used productively and fails to adequately add to output. Generating higher GDP without additional debt would require significantly improved productivity growth, growth that has eluded the developed world for nearly 20 years and has shown no sign of improvement. Productivity growth averaged 2.1% per year for decades but decelerated in 2004, and again in 2011 to an average of 0.6% per year. The leading reasons for continued weak productivity are weak levels of investment and diminishing impact of technology. Even if investment were to pick up and new technologies developed, the impact would have to be monumental to grow the economy beyond the average rate of government deficits over the long run including recessionary periods.

3. Austerity has long been considered a viable alternative but has failed to work in the past. US President Herbert Hoover chose austerity in 1930 and it led to the economy contracting further and further until FDR reversed the policies in 1933, devalued the dollar and the economy recovered. Even in the UK post the financial crisis, austerity was the key policy used. Economic growth was weak and the move was politically very unpopular. Quite often those hit hardest by it are the poorest. There has been plenty of social unrest since the Financial crisis that has come as a result of economic inequality; even since 2019 protests have taken place in France, Bolivia, Turkey, Peru, Lebanon, Thailand, the US among many others. People won’t accept cuts to public spending as billionaires grow richer through a soaring stock market. There are limits to how much tax can be raised through the wealthy, the top 1% today pay a similar average tax rate as they did in the 1950s when the top income bracket had a 91% tax rate. If raising tax on the wealthy raises limited funds, raising taxes on the poor is political suicide, cutting spending is highly unpopular and if anything has been shown to deepen the effects of a recession, there really is only one option. The stealth tax – inflation.

4. Monetise the debt is the only remaining option. Ironically it also hits the poor the hardest as it raises the cost of living above adjustments in nominal wages and thus real wages decline. However, it tends to go less noticed by the masses who are relatively financially illiterate and only notice when the devaluation is quite extreme (inflation is high). If additional debt is spent on the poor and then monetised, they may be no better off, but they will think they are. This is why $1200 in stimulus cheques was given to every person in the US who earns under $99,000, they feel as though they are being assisted by the government without realising that their purchasing power is being diminished simultaneously. The only protection against this is owning assets, and one asset outperforms all others against major devaluations: gold.

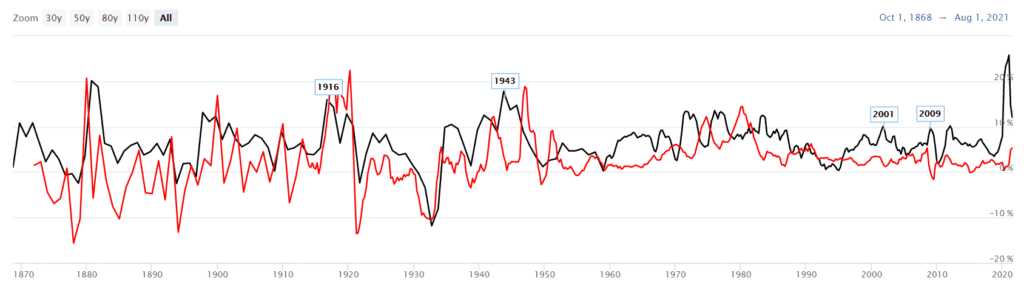

Red: YoY inflation rate (CPI) Black: YoY growth in M2 money supply

Source: https://www.longtermtrends.net/m2-money-supply-vs-inflation

The chart above illustrates the idea behind the quantity of money theory – higher rates of growth in money supply have corresponded to higher rates of inflation, especially when growth in money supply tops 10% YoY. The chart doesn’t capture the latest developments in inflation with the June CPI print hitting 5.4% YoY and 0.9% MoM. The Fed have long been touting ‘transitory’ inflation arguments, with one of the former arguments being base effects. Given we’ve had 4 consecutive months of increases larger than 0.5% MoM, it’s clear that inflation is down to much more than base effects. CPI MoM increases of 0.9% aren’t common, there have only been 3 instances since the 1970s. The other transitory inflation arguments are the reopening of the economy and supply bottlenecks. There is some truth in both of these – air fares, hotels and eating out were among the bigger contributors to the inflation print last time, but how can anyone know how long this may last? US household wealth recently hit a record $137tn through government support, rising asset prices and wage growth. Can this spending not continue for years if asset prices and wages continue to rise? US businesses have complained about lack of workers for the last few months – jobs openings are at their highest since records began in 2000. One of the reasons behind this is that employment benefits continue in most states until September, so we’ll get a better outlook on employment towards the end of the year. In the meantime, employers have had to resort to wage increases to attract workers. Wage increases tend to be sticky and put money in the hands of people who spend. Despite this, the U6 unemployment rate in the US continues to be elevated at 9.8%. This number is dominating the Fed’s policy thinking at the moment and pushes for dovish monetary policy despite the surge in inflation.

So will we get higher persistent inflation or will it be transitory? It’s very difficult to predict. Economists and central bankers have struggled for decades trying to accurately forecast inflation figures, but everything is lined up for higher inflation at some point. Critically, the Fed have signalled that they won’t raise rates until they have seen consistent inflation above 2%. In the entire history of the Fed, this has not happened before. They used to tighten in advance of inflation to prevent it surging and risk losing control. Policy was always determined by expected inflation more than past inflation. If central banks are actively encouraging higher inflation, that helps immensely with prompting its return.

Last quarter, the word ‘inflation’ cropped up more than 3,600 times in earnings calls across the World Index’s 1,557 stocks. This is the highest in more than two decades. One of the key concerns being echoed is the fragmentation in supply chains and the bottlenecks that persist. Once again there are more than 30 container ships anchored off LA waiting to berth. This is being driven by a shortage of trucks and drivers going to pick up and transport the cargo. Container rates have skyrocketed – a container from China to Europe used to cost $2000, it’s now $14,000; a container from China to the US west coast that used to cost $3,000 now costs nearly $7,000. Of course all these costs are squeezing businesses in the US who must make the decision to accept a large squeeze on their profit margins or pass the costs on. We know some costs are being passed on, that’s evident from the inflation figures that are among the highest since 1980. The global chip shortage is causing production issues in electronic goods and cars. The chairman of Daimler estimated that the shortage could last through 2022 possibly into 2023. The general message being conveyed by large company CEOs is that these pressures aren’t going to ease until later next year.

There are strong theories that changes in trade, mostly with respect to China, may lift some of the disinflationary pressures we’ve seen over the last 30 years. This was a view aired by Greenspan in 2006 who believed that China’s cheap labour supply would be over before 2030 and that would allow inflation to return. The same arguments have been made by economists Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan. Over the last 40 years China’s economic boom has lifted millions out of poverty and seen wages rise dramatically. In 1980, 80% of China’s population was rural compared to 40% today. Europe’s rural population is 28% and the USA’s is 23%. As workers move from the countryside to cities, companies expand and make use of cheap labour. This has the effect of making China the world’s cheap global factory. However, at some point you run out of labour to draw from the countryside and companies have to compete for existing labour. That puts upward pressure on wages and upward pressure on the prices of goods they manufacture. We have already reached this point in China. Since 2000, China’s real wages have been increasing by 10-15% each year and has only recently come off slightly to 7% growth. As the Chinese become wealthier, they become bigger consumers and demand higher wages, both which will pressure prices higher over the long term. The only way to continue the deflationary trends of the last 40 years would be to shift the world’s cheap factory elsewhere. India and Africa seem the obvious contenders but both have issues that render the transformation unlikely. At least, they will not fulfil that role close to the level that China has managed.

The larger forces at play through the Fed, supply bottlenecks and China suggest that inflation could be more persistent throughout this coming decade. Central Banks globally have benefitted from 4 decades of disinflationary forces and as a result, may now be overestimating their ability to control it. If supply chain disruption or China’s growth beyond manufacturing goods at rock bottom prices causes prices to rise, the cure for it is to fix the supply chains or move manufacturing to new countries with cheaper labour costs. Raising rates will stymmie demand but it doesn’t fix the inherent issues driving inflation. I think it’s certainly possible that the Fed and other Central Banks get a bit of a shock when they realise that their tools for fighting inflation aren’t as sharp as they had hoped. Let’s not forget the tools that failed through the 1970s – rate hikes, the infamous ‘Whip Inflation Now’ Government scheme that appealed to the people to stop spending. There were wage and price controls. None of these worked until the last tool in the box was the giant sledgehammer used by Paul Volcker that involved raising rates to the highest level ‘since the birth of Jesus Christ’.

Fed policy is actively seeking inflation

The September Fed meeting announced the upcoming tapering. A dot plot released at the June Fed meeting showed expectations for rates to go up not once, but twice, by the end of 2023. If inflation continues as it has, they’re going to need more than two rate hikes and some tapering to tame it. Any ideas of tightening from the Fed are driven purely by inflation concerns, yet it has been negatively impacting gold. The Fed is about as dovish as a central bank can be under the circumstances. Immediately after the dot plot release in June, Powell advised everyone to take the dot plot with a huge pinch of salt, because forecasting policy 2 years out is unpredictable. He insisted that inflation was transitory and the Fed was a long way from reaching their goals (that referred to the 9.8% unemployment figure). Even as CPI has climbed to 5.4% in July, the transitory inflation narrative is still being pushed. Never has the Fed tried so explicitly hard to overheat the economy. Normally the Fed will err on the side of caution when it comes to inflation but they’re attempting to learn lessons from the 08 recovery where inflation never appeared and arguments were made that the Fed tightened too quickly. This has created complacency, nobody now thinks sustained inflation is possible. This includes most of the investing world who agree with the Fed’s transitory narrative. 10 year treasury yields are 1.34, putting real yields at about -4% based on CPI and -1% based on breakevens. The last time real yields based on CPI plunged to -4%, gold went up 6x from 35 to about 200 in 1974, then from 200 to 800 in 1980 when real yields plunged to -4% a second time. You’d be forgiven if you thought a similar plunge in real yields this year might send gold up a similar amount, from 1700 to around 5000. The reason is that nobody else thinks inflation is here to stay – the probability of more sustained inflation being implied by the market is zero. The macro outlook for gold hasn’t been this positive since the 1970s and yet nobody is buying. I have to say I’m surprised gold hasn’t performed considerably better so far this year, but if the market shifts in its beliefs about inflation, the upward moves could be very strong indeed. Even if inflation does prove to be transitory, the US will continue to run negative real yields for many many years. There is no doubt the Fed and Government will run loose monetary and fiscal policies for as long as they can get away with it. The US can’t afford positive real rates, its debt burden is too high.

The combination of nominal yields and inflation as discussed above leads to the most important factor for gold – real yields. I cannot see how it’s feasible for real yields to be positive for any length of time over the next few years. A 1% increase in real yields would result in an additional $280bn cost to the treasury, that’s over 6x the $60bn spent on education in 2019. Debt/GDP in the US now stands at 125%, the highest it has ever been and higher than its previous peak of 118% reached in 1946. For the US to avoid sovereign debt issues, it needs to have negative real yields. The more negative real yields are, the more quickly they can reduce debt/gdp. As I’ve said above it’s difficult to predict inflation but given real yields must remain negative, the outcome can come one of two ways. Either we do see higher inflation (5%+) over the next few years in which case yields will rise with it and gold could explode quite rapidly. Or inflation will remain subdued (around 2%) and nominal yields will get driven back towards 0. In this case, I suspect gold will continue to grind higher over the next few years making new highs, but the moves will be less explosive. Frankly, either outcome is good for gold and excellent for gold miners.