china's disinflation China’s growth spells the end of a disinflationary force that opens the door for inflation

Report by: Ben Jones Published: 9th October 2021

Key points:

China has passed the Lewis turning point – wages are rising and this will put upwards pressure on the prices of goods manufactured there

China’s growth in wages will result in more global inflationary pressure over the next couple of decades

There is no suitable substitute for China’s cheap manufacturing prowess – India and Africa are obvious candidates but suffer shortfalls

China’s strained relations with the rest of the world are likely to continue and disrupt supply chains

Over the last four decades, China’s growth as a major manufacturer of global goods has been a disinflationary force on the global economy. The world has enjoyed cheap goods produced by cheap labour but China’s progression beyond the Lewis turning point has seen rising wages and a fall in the working age population. Alongside decoupling from the US that has seen slowing in globalisation, this spells an end to deflation and invites the return of inflation.

From 1990-2017, increase in the working age population (15-64) in China outpaced the combined increase of Europe and the USA by over 4x – China’s increasing 240 million versus less than 60 million between Europe and the USA. At the same time, the fall of the Soviet Union unleashed another 200 million workers on the global economy. This huge labour supply shock has provided the world with an abundance of cheap labour that has been able to manufacture goods or provide services at low costs. However, as China and Eastern Europe has developed, this low cost labour is no longer low cost and the result of this is going to be higher inflation. The only way to continue as we have for the last 40 years would be to release another abundance of cheap labour on the world, and allow them to take the cheap manufacturing mantle from China. The only options are Africa and India but both suffer from issues that make this transition difficult and it’s unlikely they’ll be able to fill China’s colossal shoes.

In his 2007 autobiography, Alan Greenspan predicted that China’s development beyond the Lewis turning point would likely see inflation return before 2030. But what is the Lewis turning point? It’s the point at which agricultural and rural labour is fully absorbed into the manufacturing sector. Every country that has been through some form of industrial revolution has passed the Lewis turning point. It’s important because before this point is reached, investors and businessmen will set up businesses that employ cheap labour to produce goods at competitive prices. As they expand and become more profitable, they hire more people. However, to do this, they needn’t raise wages. Instead they draw on a migration of poverty-stricken agricultural workers who move to the manufacturing sector in search of a better living than they’d get through subsistence farming. In the early stages, this excess supply of rural labour is in abundance. Investors, motivated by growing profitability, invest more to expand and keep the majority of profits as wages stay low driven by the excess supply of migrating labour. This opens up a deep wealth divide that has historically prompted strikes, union action and social divisiveness. However, eventually businesses hit a turning point – they run out of cheap labour. This is the Lewis turning point. Anyone willing to move to the manufacturing sector has already done so. The relative lack of new workers in manufacturing provides labour there with more bargaining power and they can demand higher wages. Businesses wishing to expand must now compete with each other for labour and this pushes wages up. They also begin to invest more in capital as the relative cost of labour to capital increases. It allows workers to become more skilled and productive which pushes wages higher again. As wages rise, the cost of production rises and this cost gets passed on to end consumers. This continues until a competitive advantage is lost and basic manufacturing transfers to another low cost country. In the meantime, the depletion of rural labour means farm workers earn more bargaining power and are able to demand higher wages. All workers spend more money in other areas of the economy which begin to develop and the country transitions towards more advanced manufacturing or services.

In a report published by Zhang and Yang, they estimate China passed the Lewis turning point in 2010. To give some indication of how wages in China have evolved, the ratio of wages for US to Chinese workers was 34.6 in 2000, it dropped to 5.1 by 2018. China’s average annual income is up 10 fold over the last 20 years, far more than any advanced economy. Their share of global manufacturing has increased from 8.7% in 2004 to 26.6% in 2017. Throughout this period, prices of durable manufacturing goods have fallen regularly in most developed economies. This deflationary pressure has been so significant that Central Banks have consistently lowered rates and still haven’t created enough inflation to hit their 2% targets. Under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, China started by creating economic zones in 1978 that allowed foreign direct investment (FDI) to partner with Chinese firms as joint ventures. Land was subsidised and infrastructure and power networks were prioritised. The west provided the capital and technology, China provided the labour. FDI expanded from $5bn in 1990 to $50bn by the late 1990s. China joined the WTO in 2000 and this marked an important step for China’s evolution as a global exporter. This allowed them to trade with the rest of the world on low or zero tariffs. However, China has now passed this peak and is transitioning to a more developed economy. China’s current account surplus peaked in 2007, their GDP growth peaked in 2012, their working age population has been shrinking since around 2017 and will continue to do so. Manufacturing made up nearly 32% of GDP in 2012 and has been shrinking since to under 27% in 2019. China’s rural population as a proportion of the total population has declined to 39% from over 80% in 1980. This compares to 25% for the EU and 17% for the US. Chinese wages now exceed nearly all emerging economies and will continue to grow, so the only choice is to accept higher prices or to shift manufacturing elsewhere. But that’s far more easily said than done.

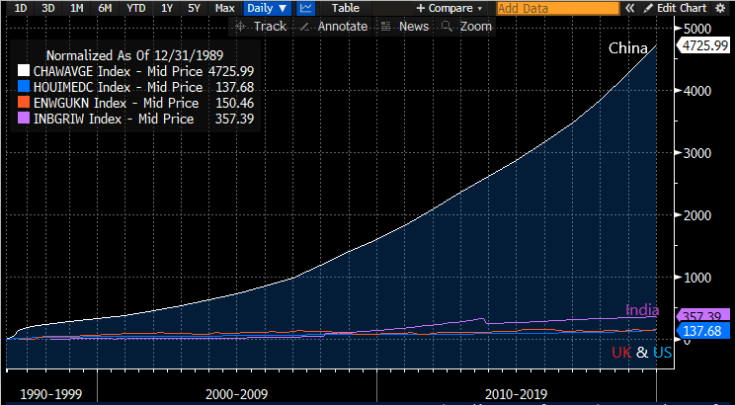

The chart below shows wage growth from 1990 – now across China, USA, UK and India. India’s data is for rural wages and data there starts only in 1998 so it’s a little understated on the chart. It’s hard to find perfectly comparable data but the point is made – China’s wage growth (+4,726%) has far exceeded the UK (+150%), US (+138%) and India’s (+357%) since 1990.

Source: Bloomberg

One possible solution to continuing the disinflation of the last 40 years is to move low level manufacturing to countries that still have cheap labour and would have a competitive advantage. Most countries don’t offer the scale that China does – this is true of Vietnam and Bangladesh which combined have a population less than 20% of China’s. The two most obvious candidates are India and Africa – they both have large, young populations. However, they both suffer from problems that make this economic transfer unlikely. Africa has a disjointed social structure and poor internal movement of people and capital. It’s made up of 54 countries each with individual policies and frictions, different languages and different cultures. They’re also at varying levels of economic progress. But the two key factors for Africa are a total lack of administrative capital and very poor human capital. African countries score among the worst for corruption and contract enforcement. Most of Africa ranks in the bottom quartile for human capital, most African countries have literacy rates below 75% with a handful below 40%. It doesn’t create an ideal environment for foreign investment when you’re likely to be stifled unless bribes are paid to corrupt officials and you can’t rely on courts to enforce contracts or fairly resolve disputes. India, as one country, suffers from less of a problem with internal movement of people and capital. Its human capital ranks higher than Africa’s although it still only ranks 116th out of 174 countries in the World Bank’s Human Capital Development Index. India has long suffered from problems with bureaucracy, only recently they increased the size of firms that could fire employees without government approval from 100 to 300. A survey by LocalCircles found that Indian startups worry more about bureaucracy than they do about funding or growth. McKinsey found that obtaining construction permits took twice as long to procure compared to other emerging economies. India still ranks poorly on contract enforcement, placing 163rd out of 190 countries. These issues have been long-standing and it’s not clear how they’ll be resolved any time soon.

As China has developed, it has started to challenge the US as a global power. China has the world’s largest population, second largest economy and largest army (it is still generally considered to be less powerful militarily than the US but not many really want to find out). This challenge has led to friction between the US and China. Friction tends to start as trade wars and technology wars before the possibility of a military war, and we’ve already seen examples of trade and technology wars – Donald Trump wasn’t particularly subtle about it. Governments are now taking harsher stances against foreign businesses. The US isn’t allowing Huawei to operate there based on security and spying concerns and has urged Europe to follow suit. The US is looking at delisting Chinese stocks that don’t open their books to US regulatory scrutiny. The UK is looking at forcing the sale of Chinese ownership in a nuclear power plant to other investors. China has forced foreign businesses into joint ventures with Chinese firms where accusations of IP theft have been rife. Chinese courts have been overwhelmingly favouring Chinese companies over foriegn companies when disputes are raised, and have now tried issuing penalties to foreign companies who bring these disputes to foreign courts. China has banned many companies such as Google, Facebook and media outlets. This is partly due to extremely tight government control of media and a desire to protect Chinese businesses from foreign competition. China has also raised tariffs on Australia for their criticism over China’s failure to allow the WHO entry to Wuhan and form any fair investigation into the origins of Covid. Political tensions have risen from China’s imprisonment of Uyghur muslims in work camps and their retaliation of Meng Wanzhou’s arrest with the arrest of two Canadian executives on trumped-up charges of spying. China has also increased their military presence in the South China sea and has been more aggressive in invading Taiwanese airspace. All of this is leading to a global decoupling between China and the rest of the world. This is likely to continue over the course of this decade and the impact will increase frictions in trade that result in the alteration of supply chains and higher prices for goods globally.

These large changes are slow-moving so China’s development won’t be the cause for inflation to increase dramatically over the next couple of years – you can look to fiscal policy, monetary policy and shorter term supply chain issues for explanations there. But it does establish a longer term trend that is under-appreciated now and removes the linchpin for a world in perpetual disinflation. It opens the door for a more inflationary environment going forward and those who think that inflation will always be low or transitory may be in for a surprise.